GRAF -- neural graph features for performance prediction

Introduction

In our ICML paper Surprisingly Strong Performance Prediction with Neural Graph Features, we introduced neural graph features (GRAF) – simple features such as path lengths or operation counts that outperform existing complex predictors.

Code

To reproduce experiments from the paper, use the repo zc_combine. We also provide a refactored version of the code for practical use in the repo GRAF.

How to cite our paper

Gabriela Kadlecová, Jovita Lukasik, Martin Pilát, Petra Vidnerová, Mahmoud Safari, Roman Neruda, & Frank Hutter (2024). Surprisingly Strong Performance Prediction with Neural Graph Features. In Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning.

@inproceedings{

kadlecov{\'a}2024surprisingly,

title={Surprisingly Strong Performance Prediction with Neural Graph Features},

author={Gabriela Kadlecov{\'a} and Jovita Lukasik and Martin Pil{\'a}t and Petra Vidnerov{\'a} and Mahmoud Safari and Roman Neruda and Frank Hutter},

booktitle={Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning},

year={2024},

url={https://openreview.net/forum?id=EhPpZV6KLk}

}

Prerequisites

For reading this blog post, it might be useful to know the basics of zero-cost proxies. You can read a blog post [2] or look at the NAS-Bench-Suite-Zero paper [1].

Motivation

Zero-cost proxies have quickly gained in popularity as fast-to-compute scores that correlate with network performance. This enabled performance estimation without any network training at the cost of few minibatch passes.

Previous works discussed the strengths and weaknesses of zero-cost proxies (ZCP) [1, 2]. As ZCP do not require network trainings, they provide very fast estimates out of the box. They can also be used in model-based prediction, including in transfer of the predictors to new datasets [3, 17].

The flip side is that the ZCP scores have inconsistent correlation across search spaces – they can be great on NB201 and CIFAR-10, but poor on NB301 and CIFAR-10 [4, 5, 6]. Also, it is poorly understood why they correlate with the performance, and they exhibit biases with network properties (e.g. operation count).

In our work, we analyzed the biases of zero-cost proxies. We discovered that some zero-cost proxies not only correlate with operation counts, sometimes they are even directly proportional to the number of convolutions!

Inspired by the findings, we proposed neural graph features (shortly GRAF) that describe the structure of the cell and enable interpretable state-of-the-art performance prediction.

Let’s delve into the details!

Zero-cost proxy shortcomings

To better understand why zero-cost proxies (ZCP) correlate so well with the validation accuracy, we want to look at scores and validation accuracies of many networks from a single search space. Conveniently, NAS-Bench-Suite-Zero (NB-Suite-Zero) contains precomputed ZCP for multiple benchmarks and tasks [1].

We first look at NAS-Bench-201 (NB201) and CIFAR-10 [4, 6] – a frequently used benchmark and dataset pair, where multiple proxies have a notably large correlation with the validation accuracy. NB-Suite-Zero contains ZCP scores of all possible architectures from the search space.

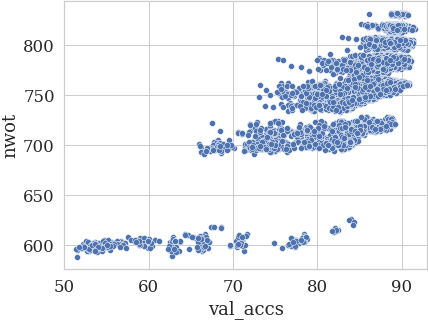

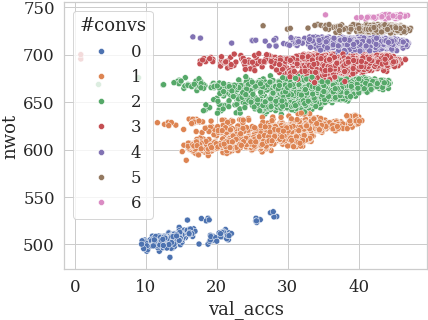

In the figure below, we plot the NASWOT (denoted nwot [8]) scores against validation accuracy. We see that some clusters are formed – what could they represent?

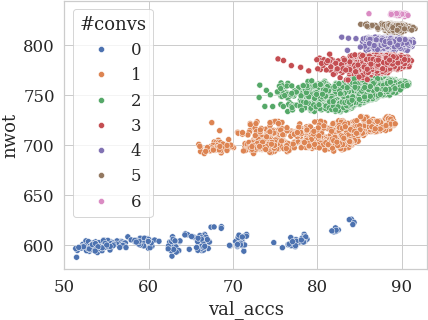

We examined networks in individual clusters, and we saw a pattern – all networks contained the same number of convolutions! We plot the scores again, this time coloring the networks by the number of Conv1x1 + Conv3x3 in the architecture:

The clusters could also be divided in half based on whether there is more Conv3x3 or Conv1x1.

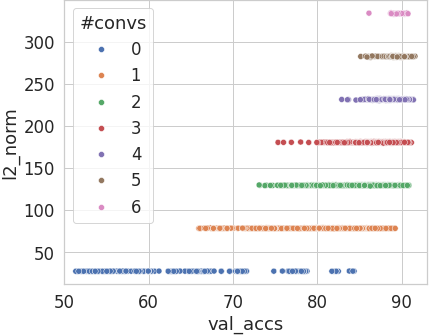

The behavior is even more pronounced for l2_norm [1]:

The ZCPdo not exhibit these properties on NB301 (based on DARTS), and on NB101, the regularities are smaller. The finding is however still important given how often NB201 is used for the evaluation of NAS algorithms or new zero-cost proxies. We show more examples at the bottom of the blog post.

GRAF

As we saw in the previous section, the number of convolutions has a notable correlation with the CIFAR-10 validation accuracy. This made us think – what if we collect other graph properties and use them along with the operation counts in model-based prediction? How good will the prediction be?

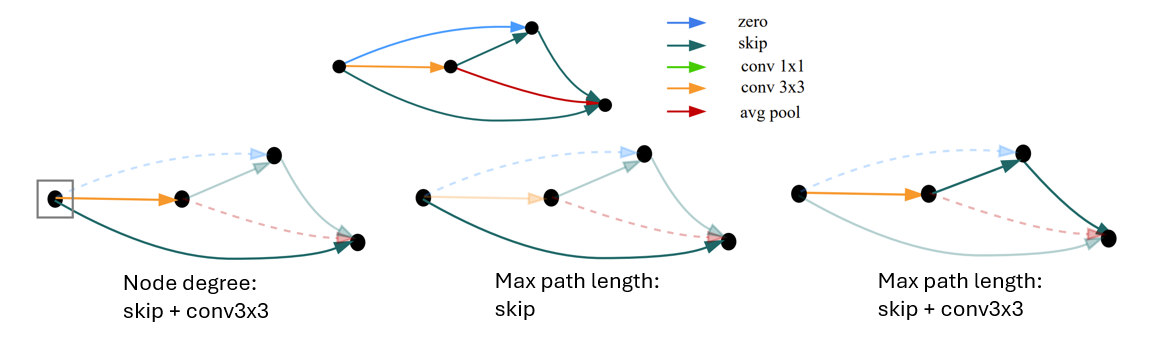

We collected the following neural graph features (GRAF):

- operation counts

- minimum path length over operations \(O\)

- maximum path length over operations \(O\)

- input/output node degree counting operations \(O\)

- average input/output node degree across all nodes (counting \(O\))

\(O\) is a subset of the full operation set \(\mathbb{O}\), and we compute them for all subsets of \(\mathbb{O}\).

Example features:

-

max_path_(conv1x1, conv3x3)(maximum path over convolutions) -

min_path_(skip)(existence of shortcuts - is there a skip to the output?) -

node_degree_(conv3x3)_in_degree(how manyconv3x3are connected to the input?)

We can use these features as an encoding of the networks from the search space, and use it for model-based prediction. First, we sample \(N\) networks for the train set, and compute their GRAF features. Then, we fit a random forest predictor on the features and corresponding targets (e.g. validation accuracy).

We compare the GRAF encoding also with the set of all ZCP from NB-Suite-Zero, and with the one-hot encoding – one-hot encoded operations along with the flattened adjacency matrix – and with their combinations.

Let’s look at the results for NB101, NB201 and NB301 [9, 4, 5] (all for CIFAR-10) and 1024 train networks (all encodings that contain GRAF are in blue):

We see that GRAF outperforms both ZCP and one-hot, and the combination of ZCP + GRAF has the overall best results!

GRAF also performs well on TransNAS-Bench-101 micro tasks, for example on the autoencoder task (sample sizes 32, 128, 1024) [14]:

Results on other tasks and sample sizes are included in the paper. Also, we present there a variant of GRAF for Trans-NAS-Bench-101 macro [14].

In the next section, we will mostly use GRAF and ZCP together (as they perform the best when used jointly).

Interpretable prediction

The good performance is not the only thing where GRAF shines – since the features are intuitive , and we use a tabular predictor, we can leverage interpretability techniques like SHAP [10].

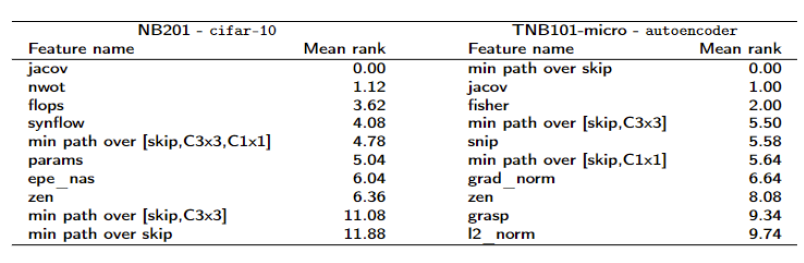

For every feature and ZCP, we compute the SHAP feature importance, and compute mean rank over 10 runs. Then, we return 10 ZCP or GRAF with the lowest rank:

We see that features and ZCP that are the most important for CIFAR-10 prediction are quite different from those that are influential on the autoencoder task.

Comparison with existing methods.

To compare GRAF with existing predictors, we followed the same setup as in the performance predictor survey [11]. We use the ZCP + GRAF variant as it had the best performance, and also include an XGBoost predictor.

The first experiment was performance prediction across various train net sample sizes. Here, we show the results on NB101 and CIFAR-10 [9, 6]:

ZCP + GRAF outperformed all predictors across all sample sizes, including complex predictors like graph neural networks or SemiNAS – a semi-supervised LSTM predictor [12].

The second experiments compared predictors in search settings – they were used as surrogates in Bayesian optimization (refer to our paper for more details). We show the results for NB201 and ImageNet16-120 [3, 7]:

ZCP + GRAF is more sample efficient than all the other predictors.

It is important to note that some models still outperform ZCP + GRAF in some settings. SemiNAS performs on par with ZCP + GRAF on NB201 + CIFAR-10 search [12, 3, 6]. BRP-NAS – a graph neural network (GNN) predictor – can be combined with ZCP + GRAF for best results on NB301 [13, 5]. However, in most cases the GNN models perform the same as ZCP + GRAF + random forest, while taking longer to train.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we introduced GRAF – neural graph features that enable interpretable tabular performance prediction. We highlighted the main ideas along with its strengths and results.

The main weakness of GRAF is that it has to be devised every time a new search space is designed. For most graph-based search spaces, the general idea of using paths, node degrees and operation counts can be easily applied (although due to different operation sets, transfer is not possible). It is also possible to use large language models for new GRAF proposal, notably for macro search spaces.

Overall, we see GRAF as an important baseline for more complex method and a valuable interpretability tool for neural architecture search.

More details can be found in our paper

- even more results across popular search spaces

- macro search space features

- longer discussion

- results when combined with BRP-NAS - a graph neural network predictor

- results on hardware tasks (energy, latency) and robustness tasks [15, 16]

[1] Arjun Krishnakumar, Colin White, Arber Zela, Renbo Tu, Mahmoud Safari, & Frank Hutter (2022). NAS-Bench-Suite-Zero: Accelerating Research on Zero Cost Proxies. In Thirty-sixth Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track.

[2] White, C., Khodak, M., Tu, R., Shah, S., Bubeck, S., & Dey, D. (2022). A Deeper Look at Zero-Cost Proxies for Lightweight NAS. In ICLR Blog Track.

[3] Yash Akhauri, & Mohamed S Abdelfattah (2023). Multi-Predict: Few Shot Predictors For Efficient Neural Architecture Search. In AutoML Conference 2023.

[4] Dong, X., & Yang, Y. (2020). NAS-Bench-201: Extending the Scope of Reproducible Neural Architecture Search. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

[5] Arber Zela, Julien Niklas Siems, Lucas Zimmer, Jovita Lukasik, Margret Keuper, & Frank Hutter (2022). Surrogate NAS Benchmarks: Going Beyond the Limited Search Spaces of Tabular NAS Benchmarks. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

[6] Alex Krizhevsky, Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images, 2009.

[7] Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.-J., Li, K., & Fei-Fei, L. (2009). Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 248–255).

[8] Joseph Mellor, Jack Turner, Amos Storkey, & Elliot J. Crowley (2021). Neural Architecture Search without Training. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

[9] Ying, C., Klein, A., Christiansen, E., Real, E., Murphy, K., & Hutter, F. (2019). NAS-Bench-101: Towards Reproducible Neural Architecture Search. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 7105–7114). PMLR.

[10] Lundberg, S., & Lee, S.I. (2017). A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (pp. 4765–4774). Curran Associates, Inc..

[11] White, C., Zela, A., Ru, R., Liu, Y., & Hutter, F. (2021). How Powerful are Performance Predictors in Neural Architecture Search?. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 28454–28469). Curran Associates, Inc..

[12] Luo, R., Tan, X., Wang, R., Qin, T., Chen, E., & Liu, T.Y. (2020). Semi-Supervised Neural Architecture Search. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 10547–10557). Curran Associates, Inc..

[13] Dudziak, Ł, Chau, T., Abdelfattah, M., Lee, R., Kim, H., & Lane, N. (2020). BRP-NAS: prediction-based NAS using GCNs. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates Inc..

[14] Duan, Y., Chen, X., Xu, H., Chen, Z., Liang, X., Zhang, T., & Li, Z. (2021). TransNAS-Bench-101: Improving Transferability and Generalizability of Cross-Task Neural Architecture Search. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 5251–5260).

[15] Chaojian Li, Zhongzhi Yu, Yonggan Fu, Yongan Zhang, Yang Zhao, Haoran You, Qixuan Yu, Yue Wang, Cong Hao, & Yingyan Lin (2021). \HW-\NAS-Bench: Hardware-Aware Neural Architecture Search Benchmark. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

[16] Steffen Jung, Jovita Lukasik, & Margret Keuper (2023). Neural Architecture Design and Robustness: A Dataset. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations .

[17] Lukasik, J., Moeller, M., and Keuper, M. An evaluation of zero-cost proxies – from neural architecture performance to model robustness. In DAGM German Conference on Pattern Recognition, 2023.

Bonus material

Zero-cost proxies and the number of convolutions

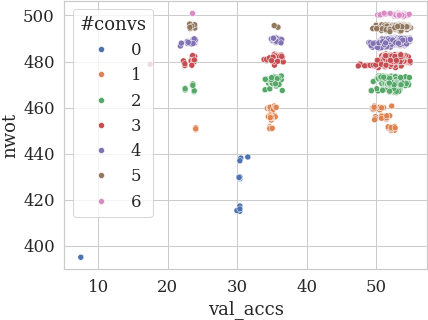

When we again plot nwot by validation accuracy for NB201, this time for ImageNet16-120 [7], we can see why nwot has a lower correlation on this dataset - the distribution of validation accuracies is more stretched.

Finally, we see why zero-cost proxies have a poor performance on TransNAS-Bench-101 micro tasks – the validation accuracy does not depend on the number of convolutions as on CIFAR-10 (here plotted for the class_scene task) [14].

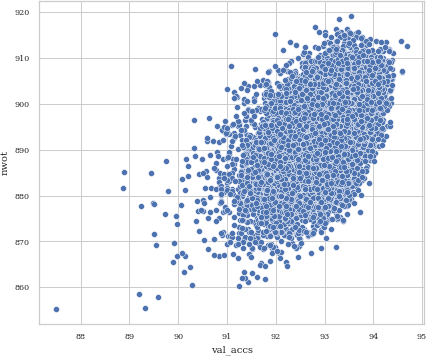

For NB301 (a subset of darts), no clusters are formed for the ZCP (below we plot nwot by CIFAR-10 validation accuracy):

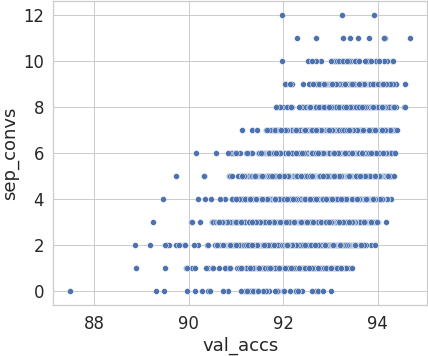

However, the number of separable convolutions is a competitive predictor:

Using ChatGPT for feature proposal

During the reviewing process, one of the reviewers asked about potential automatic discovery of features – if a new search space differs from the previous spaces, it is necessary to design new GRAF (macro) features.

To address the question, we briefly experimented with GPT4 to obtain suggestions for macro features on an unexplored (hypothetical) transformer search space. The outputs look promisingAn excerpt of our experiment is listed here:

Prompt: What could be useful characteristics of neural architectures that can be computed syntactically and that are predictive of the architecture’s performance?

(… ommiting outputs related to convnets …)

Prompt: How about transformers?

ChatGPT output:

Transformers, initially introduced for natural language processing tasks, have shown remarkable success across a wide range of domains including image processing, audio signal processing, and more. Unlike convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that process data sequentially and locally, transformers use self-attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different parts of the input data globally. For transformer architectures, several syntactic characteristics can be computed and are predictive of the architecture’s performance:

- Number of Transformer Layers (Depth): This refers to how many transformer blocks or encoder/decoder pairs are stacked. More layers allow the network to learn more complex relationships at the cost of increased computational complexity and potential challenges in training stability.

- Model Dimensionality (d_model): The size of the embeddings and the hidden layers within each transformer block. Higher dimensionality can increase the capacity of the model to learn complex relationships but also increases the number of parameters and computational requirements.

- Number of Attention Heads (h): Transformer models use multi-head attention mechanisms to allow the model to focus on different parts of the input for different reasons simultaneously. The number of heads determines the width of the model’s attention and influences the model’s ability to capture various aspects of the data.

- Size of the Feed-Forward Networks: Each transformer block contains a position-wise feed-forward network. The size of these networks (often denoted as d_ff in literature) is a critical parameter that affects the model’s capacity and its computational demands.

- Vocabulary Size: For models trained on textual data, the size of the vocabulary affects the embedding layer’s size and thus the number of parameters. For tasks involving other types of data, analogous parameters might define the input feature space’s dimensionality.

- Sequence Length: The maximum sequence length that the model can handle. This impacts the computational complexity, especially in the self-attention mechanism, where the complexity grows quadratically with the sequence length.

- Positional Encoding Scheme: Transformers use positional encodings to incorporate information about the order of the sequence elements. The choice of positional encoding (learned embeddings vs. sinusoidal functions) does not add parameters but can influence performance.

- Attention Mechanism Variant: Beyond the standard scaled dot-product attention, there are variants like local attention, sparse attention, or the recently popular efficient attention mechanisms that reduce computational complexity. The choice and configuration of the attention mechanism can significantly impact model performance and efficiency.

- Regularization Techniques: Identifying the presence of regularization techniques such as dropout, attention dropout, and layer normalization within the transformer. These techniques are crucial for preventing overfitting and ensuring stable training.

- Parameter Initialization Scheme: Transformers are sensitive to the initialization of parameters. The chosen scheme (e.g., Xavier, He initialization) can significantly impact the training dynamics and the final model performance.

- Computational Complexity: Estimating the computational complexity, especially in terms of FLOPs (floating-point operations) for the self-attention mechanism and the overall forward pass. This complexity impacts training time, inference speed, and the feasibility of deploying the model in resource-constrained environments.

These characteristics provide a framework for understanding, comparing, and optimizing transformer architectures. They influence the model’s learning capacity, computational efficiency, and applicability to different tasks and datasets.